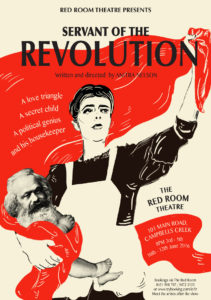

The creative non-fiction play Servant of the Revolution speculates — in women’s liberationist and socialist ways — on the relationship between Karl Marx and his household servant Helene Demuth (best known as ‘Lenchen’) who bore his illegitimate child, Freddy. Engels covered for Marx by claiming Freddy’s paternity.

The creative non-fiction play Servant of the Revolution speculates — in women’s liberationist and socialist ways — on the relationship between Karl Marx and his household servant Helene Demuth (best known as ‘Lenchen’) who bore his illegitimate child, Freddy. Engels covered for Marx by claiming Freddy’s paternity.

Servant of the Revolution takes Lenchen’s point of view.

Essentially a two-hander between Lenchen and Engels, their dialogue is interrupted by Marx’s youngest daughter, Tussy whose everyday dilemmas reflect the intriguing dynamics of the Marx household.

Endorsements

Servant of the Revolution presents and analyses, in a concentrated, real time situation, the crosscurrents of lofty idealism vs. cruel pragmatism and enduring love vs. enduring duty. These forces swirl about and trap Lenchen, the faithful servant of the Marx family and the mother of Karl Marx’s illegitimate son.

Cunningly, Anitra Nelson puts Engels, not Marx, on stage as go-between and manipulative fixer when Lenchen wants to see and know her boy, long since fostered out and now a man. Engels, the prophet of revolution and freedom, pleads Victorian respectability to prevent her. He plays on the servant’s own devotion to the cause and on her indestructible love for her master, Marx.

At the end, a cheery Mrs Marx — who knows, but chooses not to know — returns home and Lenchen is where she began: the faithful servant, who will serve to the end. Her yearning can’t break through and she can’t break out.

An ironic slice of imagined biography, based on known facts, about how revolutionaries can exploit the proletariat, and are human, all-too-human, too.

— Award-winning screenwriter and script editor Michael Brindley

The major impression after watching Servant of the Revolution is that one has been given a unique and disturbing glimpse into the specific circumstances and personal conduct of Karl Marx and his family.

The domestic arrangements and the personal/class relationships portrayed in the play appear detailed and authentic. The central dialogue between Engels and Helene Demuth is lively, compelling and unsettling. Every character has an individual voice and manner.

By placing the action in the kitchen, the author is able to sharpen and foreground the awkward, confronting class tensions. That Marx himself doesn’t appear and others are left to pick through the consequences of his actions, creates tension and a degree of justified anger in the spectator. His absence and that of the unacknowledged son, has a potent theatrical effect. All in all, Servant of the Revolution reveals a formidable level of research and a commitment to the complexity and truth of a potentially tragic situation. It provokes consideration about issues of class, gender and politics that remain largely unresolved and unacknowledged today. — Actor-director Paul Hampton

Background: Why?

At the end of March 1851, in one of communist revolutionary Karl Marx’s regular letters to his best friend and colleague Frederick Engels, he refers to ‘a mystère’ and a plan ‘in which you also figure’. A couple of weeks later he left Soho, London, to visit Engels in Manchester to escape domestic chaos and hatch his plot.

We are talking about those years that Marx’s wife Jenny refers to in her scant and incomplete autobiography as ‘the years of the greatest and at the same time pettiest worries, torments, disappointments and privations of all kinds’. Marx’s wife, Jenny, had just had a baby that Marx lamented was a girl, not a boy. The second of two of their children to die within a year passed away within weeks of the fifth baby’s birth, a French refugee paying for her coffin.

pettiest worries, torments, disappointments and privations of all kinds’. Marx’s wife, Jenny, had just had a baby that Marx lamented was a girl, not a boy. The second of two of their children to die within a year passed away within weeks of the fifth baby’s birth, a French refugee paying for her coffin.

Indeed, as soon as Jenny found out she was pregnant, in August 1850, she visited a wealthy relative in Holland, Lion Philips — whose progeny were responsible for Philips lighting company — landing in such a dishevilled state that Lion did not recognise her. Worse still, he rebutted pleas for money advising that her husband should find a job, if need be, in America.

Back in Soho, ‘one of the worst and hence cheapest quarters’ according to a Prussian agent, Jenny’s servant Helene Demuth — constantly referred to by the family as ‘Lenchen’ — became pregnant. In Spring 1851, it was details of this ‘mystère’ that Marx desperately needed to explain to his best friend and collaborator. Marx was living in a household where his wife had just given birth and their faithful servant was six months pregnant to him. Would Engels cover for Marx?

Media

For more, see Nelson A ‘Servant of the Revolution: The creative art of serving history and the imagination’, Hecate: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Women’s Liberation 36(1&2): pp. 137–52 and the ABC Radio National podcast — ‘Marx’s love child’, Anitra Nelson interviewed by Richard Aedy, Life Matters ABC Radio National 20 July 2009.

Script

For a copy of the script, and permission to use it in a public performance, contact me directly.

The play is also available in a German translation.

nts of Jenny and Marx were friends living in Trier. All three knew one another from childhood. Jenny and Marx became childhood sweethearts, even though Jenny was four years older than Marx. It is even possible Lenchen acted as a go-between when they were secretly engaged against both families’ wishes.

nts of Jenny and Marx were friends living in Trier. All three knew one another from childhood. Jenny and Marx became childhood sweethearts, even though Jenny was four years older than Marx. It is even possible Lenchen acted as a go-between when they were secretly engaged against both families’ wishes. o country and settled in London. She outlived Jenny Marx, nursing Marx for more than a year before he died, and then became Engels’ head housekeeper.

o country and settled in London. She outlived Jenny Marx, nursing Marx for more than a year before he died, and then became Engels’ head housekeeper. arx submitted like a lamb to this dictatorship’. Lenchen ‘rolled him around her finger’. Family members would send her on missions to ‘Moor’. While ‘he might storm and thunder ever so much, keeping everybody else at a distance, Lenchen went into the lion’s den, and if he growled she gave him such a severe lecture that the lion became meek as a lamb’. (See image of Lenchen in later years.)

arx submitted like a lamb to this dictatorship’. Lenchen ‘rolled him around her finger’. Family members would send her on missions to ‘Moor’. While ‘he might storm and thunder ever so much, keeping everybody else at a distance, Lenchen went into the lion’s den, and if he growled she gave him such a severe lecture that the lion became meek as a lamb’. (See image of Lenchen in later years.)